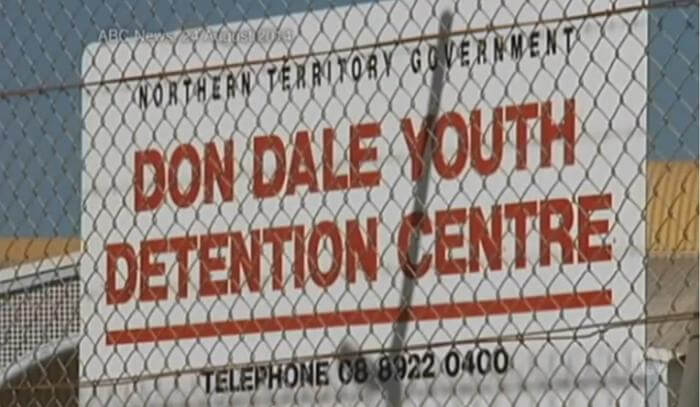

Before the Northern Territory Royal Commission begins in October, let’s take a short breather to remind ourselves what it is we’re examining. Don Dale showed us the worst of what juvenile detention can be. Four Corners broadcast footage of children as young as thirteen being abused, assaulted and belittled. These children – denied opportunities and demonised by politicians and society – became trapped in the revolving door of prison, to be re-abused by another set of guards with inadequate training. Don Dale was like a version of the Stanford prison experiment: make-believe criminals being beaten up by make-believe guards.

If the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre ever had a justification to exist, it lost it a long while ago. When the Royal Commission looks at Don Dale it will be examining the model of an unsuccessful juvenile justice system. So today, let’s look at some successful systems, and see what can be learnt for the future of youth justice in Australia.

The Scandinavian Model

In Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland, the age of criminal responsibility is 15. This means that in those countries it would be legally impossible to incarcerate a thirteen-year-old for theft (this is what happened to Dylan Voller). Rather than a penal system, these Scandinavian countries address the crimes of the very young with intensive social welfare systems. It’s been called a “cross-professional” approach, and it sees schools, social welfare officers, child psychologists, health professionals and police sharing information about any at-risk children, so that a comprehensive, individualized approach can be taken to ensuring their welfare. It is exactly the way a caring parent would try and divert their child from further errant behaviour.

So Scandinavian countries don’t treat offending children like the bane of society? How do their politicians make small talk? In the words of The Atlantic:

“[T]throughout Scandinavia, criminal justice policy rarely enters political debate. Decisions about best practices are left to professionals in the field, who are often published criminologists and consult closely with academics. Sustaining the barrier between populist politics and results-based prison policy are media that don’t sensationalize crime—if they report it at all.”

We can already hear the Hadley acolytes tapping out their objections: how do you expect to stop crime if you don’t adequately punish people? The thing is, Scandinavian countries do stop crime – it’s just that they stop it before it happens. This proactive approach results in vastly better outcomes for all parties: the victim doesn’t suffer the trauma of crime, society doesn’t have to pay to for lawyers and jailers, and the child doesn’t have their future compromised by criminal charges.

Sure, the acolytes protest, but does a softer system actually work? And would it work in New South Wales? In 2014 the Australian Children’s Commissioner, Megan Mitchell, stated that “evidence has shown that policies and preventative interventions which help to address vulnerability in children will ultimately reduce rates of juvenile offending.” On the contrary, she said, contact with the penal system actually increases the rate of reoffending, and makes it more likely that kids will commit crimes into adulthood.

The full title of the upcoming Royal Commission is the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. They’ve done one thing right already: Protection comes before Detention. Let’s make that a reality.

(Apologies for the lack of blogging. We’re going to follow the example of the Northern Territory government and blame everything on Four Corners.)

-

Peter O'Brienhttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/peterob/

-

Peter O'Brienhttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/peterob/

-

Peter O'Brienhttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/peterob/

-

Peter O'Brienhttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/peterob/