A respiratory doctor testified on Thursday that George Floyd died from a lack of oxygen.

Martin Tobin, a pulmonologist, told the jury at the police officer’s trial that he had watched videos of Floyd’s arrest “hundreds of times”.

“Mr Floyd died from a low level of oxygen,” Mr Tobin told the jury.

“This caused damage to his brain,” he said, and arrhythmia – an irregular heartbeat – which “caused his heart to stop”.

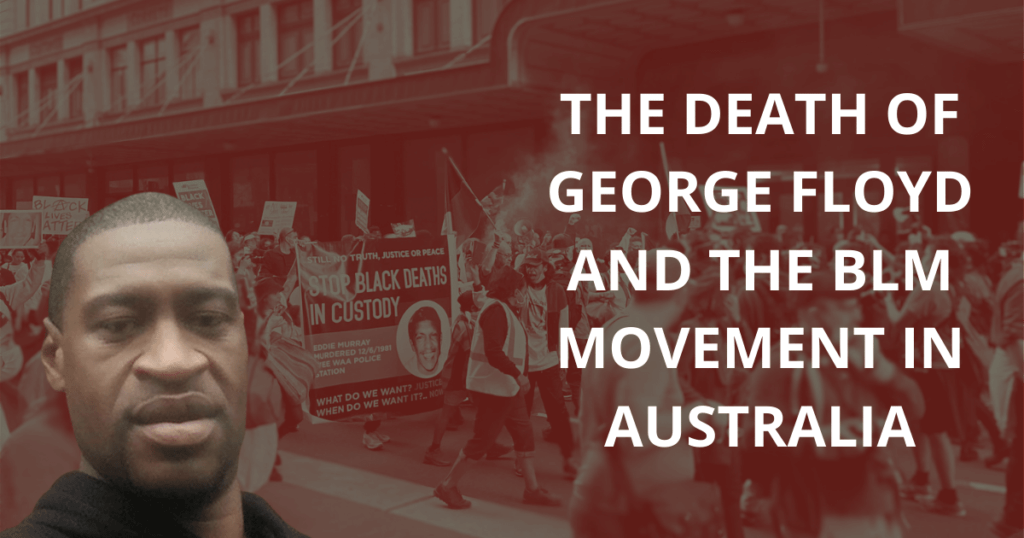

The death that rocked the world

On May 25 2020, a convenience store employee called 911 and reported that George Floyd had used a counterfeit $20 note to buy cigarettes. Shortly after, Minneapolis police officers arrested the 46-year-old black man.

Seventeen minutes after the first squad car arrived at the scene, Mr. Floyd was unconscious and pinned beneath three police officers, showing no signs of life. Footage of the incident showed Officer Derek Chauvin with his knee pressing down into the neck of Floyd.

On May 26 2020, the Police Department fired all four officers involved.

Floyd’s death sparked worldwide protests against police brutality, police racism and lack of police accountability.

The unrest began in local protests in the Minneapolis area before quickly spreading nationwide and to over 60 countries internationally, including Australia.

At least 200 cities in the U.S. had imposed curfews by June 3, while more than 30 states and Washington, D.C, activated over 62,000 National Guard personnel due to the mass unrest.

In early June 2020, soon after the George Floyd protests in the US, protests took place in Australia. Many of them focusing on the local issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody, racism in Australia and other injustices faced by Indigenous Australians.

The death of David Dungay Junior

Dunghutti man David Dungay Jr died on 29 September 2015 after guards rushed into his cell to stop him from eating a biscuit. They dragged him into another cell and held him face down and had him injected with a sedative. Before he died, he told guards 12 times that he could not breathe.

Dunghutti man David Dungay Jr died on 29 September 2015 after guards rushed into his cell to stop him from eating a biscuit. They dragged him into another cell and held him face down and had him injected with a sedative. Before he died, he told guards 12 times that he could not breathe.

David’s death was thrown into the spotlight after the death of George Floyd due to the words both used moments before their death. Those words have become a war cry for protestors.

I can’t breathe

David’s mother Leetona Dungay said that the recent Black Lives Matter movement has helped bring her son’s death to public attention.

“No-one listened to us. Something changed in the murder of George Floyd in the States. George Floyd just like my son. He was held down screaming ‘I can’t breathe’ until he died.”

Nephew of David, Paul Francis-Silva hoped the outrage being felt by Australians over George Floyd’s death would help bridge some gaps at home.

“We’re outraged about what’s happening in Minneapolis, but really us guys home in Australia need to take a stand together here, the First Nation’s people and the non-First Nations people, because they’re showing a lot of support through this as well, because they can actually see the racism and injustice against our people.”

The fight continues on deaths in custody

This Saturday 10 April is a National Day of Action against black deaths in custody.

This Saturday 10 April is a National Day of Action against black deaths in custody.

It marks 30 years since the release of Final Report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. It also showcases the lack of progress made in this space.