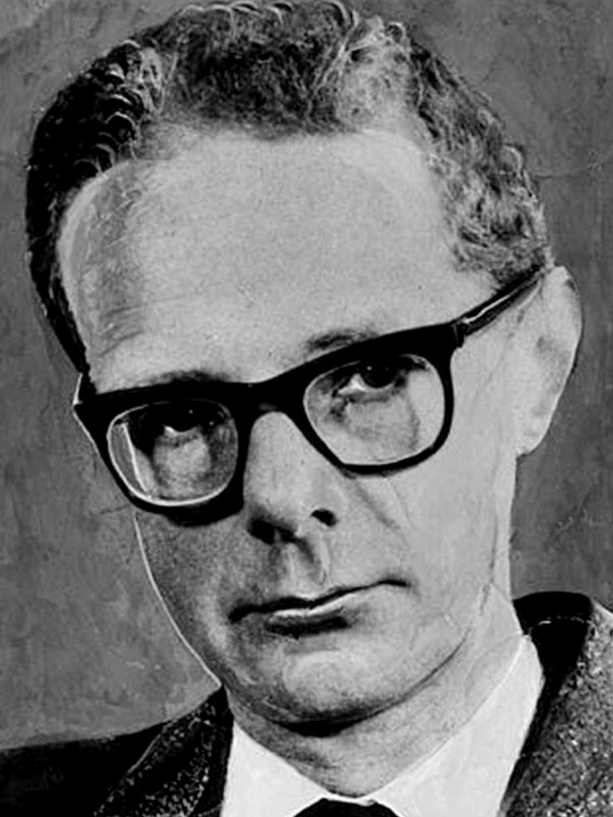

Dr George Duncan was a law lecturer at the University of Adelaide who drowned after being thrown in the River Torrens on 10 May 1972.

The men believed to be responsible for his death were police officers, who knew that the area was a well-known gay beat.

Duncan’s murder was a key catalyst in criminal reform and public awareness of police brutality.

A promising life ended due to sexual preference

A promising life ended due to sexual preference

George Duncan was born in London in 1930 to his New Zealand-born parents. Emigrating to Melbourne as a young boy, he attended Melbourne Grammar School where he graduated as dux. After numerous university degrees and a bought of tuberculosis, Duncan took up a lectureship in law at the University of Adelaide.

Six weeks into his new job, he was murdered.

Homosexuality and police brutality

In 1972, homosexuality was illegal in all states and territories of Australia. Gay or bisexual men would often meet at known ‘beats’, such at the River Torrens. These were often only known to the men involved, and police officers.

In 1972, homosexuality was illegal in all states and territories of Australia. Gay or bisexual men would often meet at known ‘beats’, such at the River Torrens. These were often only known to the men involved, and police officers.

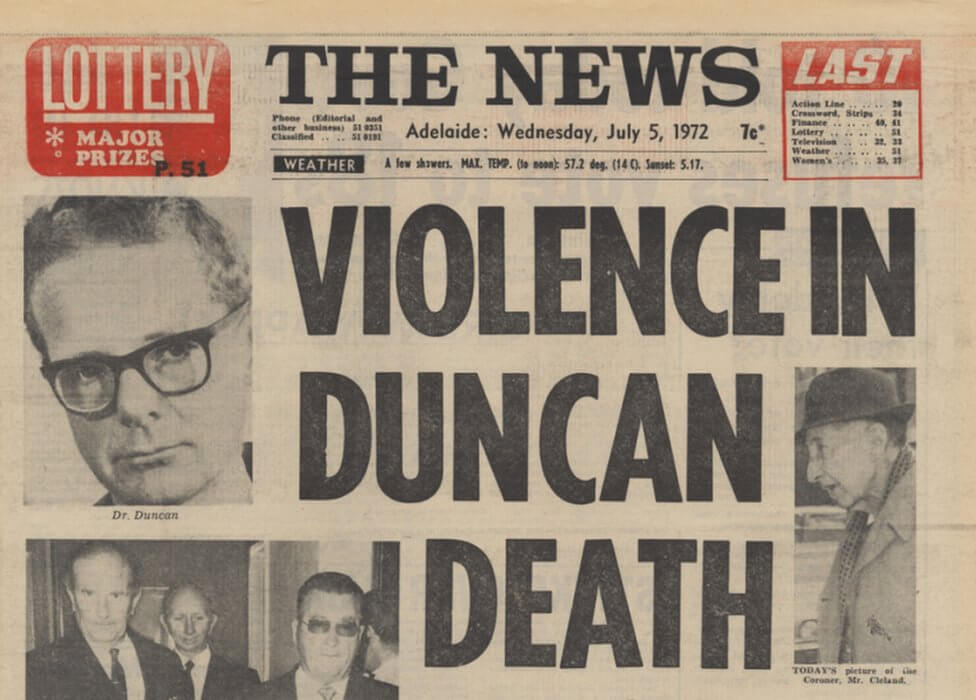

On 10 May 1972, three men, including Duncan, were all thrown into the river by a group of men in separate incidents. Duncan, unable to swim, drowned.

Witnesses declined to identify the attackers and feared for their lives. Within days, three vice squad police officers were suspected of his death.

Police officers in the area were known to be throwing gay men into the river, with ex-vice squad officer Mick O’Shea recalling the acts to SBS.

“They used to talk about it in the vice squad every bloody day of the week,” says O’Shea.

“They would brag regularly about their escapades with the gays and what they’d done to them and how they’d thrown them in the river … I said to them on a number of occasions, ‘You’ll drown one one day. You’re gunna drown one.’”

Eventually, two Vice Squad members were tried and acquitted of Duncan’s manslaughter.

Detective Chief Superintendent Bob McGowan from Scotland Yard wrote in his report that Michael Kenneth Clayton, Francis John Cawley and Brian Edwin Hudson “took part, possibly with others, in throwing Duncan, James and [Witness A] into the water but despite intensive inquiries, no further witness has been found who can assist in providing further evidence against them … there was no real intention of causing anyone’s death – this was merely a high-spirited frolic which went wrong.” This report was only tabled in parliament in 2002 after successive governments had refused to release it

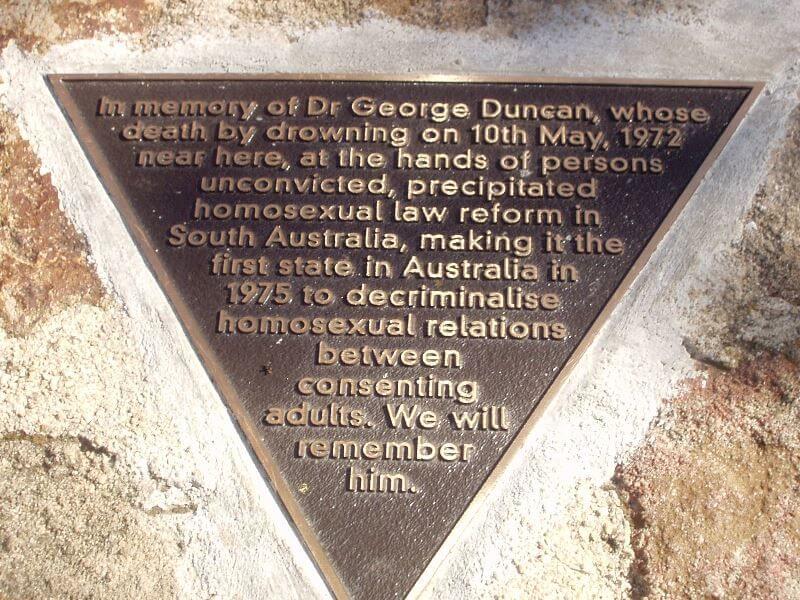

Regardless of the injustice in his case, Duncan’s death led a push to decriminalise homosexuality.

Twenty-five years of decriminalisation

In 1975, South Australia officially decriminalised male homosexuality. The ACT decriminalised it shortly after in 1976.

The first Mardi Gras was held in 1978 following a protest march and commemoration of the Stonewall riots. More than 500 people gathered on Oxford Street, calling for an end to discrimination against homosexuals in employment and housing, and an end to police brutality and harassment and anti-homosexual laws.

Police revoked the permissions granted for the parade and met the parade with police violence and arrests. After the parade was dispersing in Kings Cross, police arrested 53 of the participants. Although most charges were eventually dropped, The Sydney Morning Herald published the names of those arrested in full. This led to many people being outed to their friends and places of employment. Many of those arrested lost their jobs as homosexuality was a crime in NSW at that time.

In 1980, Victoria decriminalised male homosexuality. Victoria had, and continued to have an incredibly negative reputation for brutality of the LGBTQI community. It even kept the death penalty for the offence until 1949. Even after decriminalisation, dissident Liberal Party members ensured that “solicitor for immoral purposes” was still a crime. This saw police brutality and harassment continue well into the 1980s.

Northern Territory decriminalised homosexuality in 1983, followed by NSW in 1984, Western Australia in 1989, Queensland in 1990 and Tasmania in 1997.

Discrimination in the criminal justice system

Until 2003, New South Wales had varying ages of consent for heterosexual and homosexual relations. Following decriminalisation in 1984, legislation set the age of consent to 18. However, the age of consent for heterosexual sex was 16.

The only states to set an equal age of consent at the time of decriminalisation were SA, Victoria and Tasmania. The NT, ACT and Queensland all enacted the unequal ages. Queensland was the last state to changes the discriminatory laws, with the age changed to 16 in 2016.

Almost 50 years on from Duncan’s death, and even after criminal justice reform, the LGBTQI community still faces discrimination from sectors of the community, having only succeeded in the fight for equal marital rights in 2017.

If you have been affected by adverse police action, or believe you were unlawfully arrested or targeted, contact O’Brien Criminal & Civil Solicitors for a free consultation.