Across Australia, children as young as 10 can be arrested by police, charged with an offence, hauled before Children’s Court and locked away in a prison. In response to this, Raise the Age is a campaign for the federal, state and territory governments to do what is right and #raisetheage of criminal responsibility.

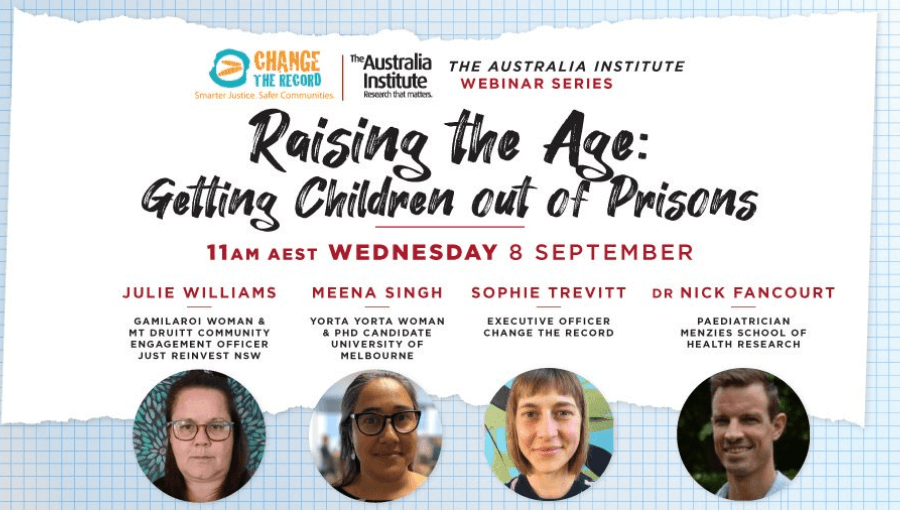

Accordingly, Australia Institute TV in partnership with Change the Record, are hosting a webinar featuring leading academics and campaigners for raising the age. Those guests include:

- Julie Williams, Gamilaroi woman and Mt Druitt Community Engagement Officer, Just Reinvest NSW;

- Meena Singh, Yorta Yorta woman and PhD candidate, University of Melbourne;

- Sophie Trevitt, Executive Officer, Change the Record; and

- Dr Nick Fancourt, Paediatrician, Menzies School of Health Research.

The webinar is taking place tomorrow, Wednesday 8 September 2021 at 11am.

Failing Australia’s Children

For a person to be responsible for a crime, they have to have the capacity to be ‘criminally responsible’. However, when it comes to children, Australia states that this occurs the day you turn 10.

In 2019, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended 14 years as the minimum age. Many countries across Europe have the minimum age as 14. Even our friends across the Tasman have a minimum of 13. However, this is except in cases of manslaughter or murder.

Here are some other countries and how they legislate on this issue:

- 12 years—Canada, Greece, Netherlands;

- 13 years—France, Israel, New Zealand (except for murder/ manslaughter where the age limit of 10 applies);

- 14 years—Austria, Germany, Italy and many Eastern European countries;

- 15 years—Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden;

- 16 years—Japan, Portugal, Spain;

- 18 years—Belgium, Luxembourg.

In January this year, the United Nations slammed Australia’s human rights record, urging the Government to shift their position on raising the age.

Australia’s youth justice and age of criminal responsibility was a strong focus for scrutiny in the review, with roughly 31 UN member states recommending raising the age.

Why does the age need to be raised?

The laws affect a large number of children. According to the AIHW, in 2018-219, more than 570 children aged 10-14 were placed into juvenile detention. Indeed, sixty-five per cent of those children were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

There are also medical reasons for raising the age. For example, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) submitted a report to the COAG in favour of raising the age. In that submission, RACP mentioned child development studies that found that children under the age of 14 lack impulse control and have a poorly developed capacity to foresee consequences.

Additionally, the RACP also highlighted that “most children in the youth justice system have significant additional neurodevelopmental delays. These children also have high rates of significant pre-existing trauma.”

According to Professors of Criminology Eileen Baldry and Chris Cunneen, juvenile detention increases a child’s risk of depression, suicide and self harm. Consequently, it leads to poor emotional development and results in poor education outcomes and fractured family relationships.

These laws also disproportionately affect children with cognitive impairments. For example, nine out of ten of young people in WA youth detention had severe impairment in at least one area of brain function, according to a 2018 study.

Raise the Age: Part of a solution-based approach

Many types of solutions have been thrown around. For example, here are some of the top solutions alongside the people who have recommended them.

- Better support through acute paediatric and general mental health services (RACP)

- Support for parents struggling with mental health and drug and alcohol issues (RACP)

- Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to develop culturally appropriate solutions within the community (RACP)

- Expansion to child protection services to support vulnerable children and their families (RACP)

- More emphasis on support services, treatment, early intervention and community-led diversion programs built on Indigenous culture (Law Council of Australia).

“Aboriginal children are strong, smart and resilient. But we know through our work at the ALS that Aboriginal children as young as 10 are targeted and taken into custody, at risk of being taken to a barbed wire facility, strip searched on entry, given limited access to peers, teachers and supports, and put in a concrete cell,” stated Warner.

Register for the Raise the Age webinar here