Four years ago, Peter O’Brien delivered a bag full of cash to two Indonesian boys in their village of Bau Bau in South-East Sulawesi.

The bag, filled with Indonesian rupiahs, was money awarded from the Courts by the Australian Government for their false imprisonment in Silverwater Correctional Complex.

How they got to be there is a story of itself.

Lured onto a people-smuggling boat, detained by Australian Authorities

Pak, 14 and Atok, 16* were lured under false pretences into crewing a boat which was going to be used by people smugglers to transport people into Australia.

“They were the unwitting crew of a people-smuggling boat. They had been fishermen since they were very young, and grew up in a fishing village in South East Asia,” Peter said.

The boat was intercepted by Australian authorities who threw the two boys into Darwin children’s immigration detention centre.

In the early hours of June 30 2011, the boys were woken up and transported to Sydney.

They were taken directly to Surry Hills Police Station and at 10:15 am they were officially arrested and charged with aggravated people smuggling.

The boys were detained at the Police Station before taken to a bail hearing at Central Local Court.

At 2:30pm bail was refused and they were transferred to Silverwater Correctional Complex.

Peter O’Brien appeared for Pak and Atok in the NSW District Court, and then later assisted them in suing the Australian Government in the Supreme Court of NSW.

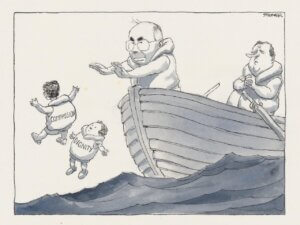

“Turn back the boats”

The rhetoric required for these practices to be set in motion was established a further ten years before Atok and Pak were detained.

After the Islamophobic backlash from 9/11, the Howard Government moved decisively to implement a range of immigration laws. Refugees and asylum seekers were identified as the ‘them’, with the ‘us’ against ‘them’ beliefs gaining traction.

Australia’s own Islamic ‘them’ – South East Asian immigrants – were swept up in harsh anti-terrorism rhetoric and political demonization.

By the time that proverbial dust had settled from the Tampa Incident and the “Children Overboard” scandal, the Draconian infrastructure that haunts Australia’s immigration system was already well established.

By the time that the Liberal Government exited office in 2007, the wheels of the machine already had bi-partisan support.

The public and the Government took a hard-line stance on people smuggling and applied the full weight of the law on anyone involved in the act.

A no-tolerance attitude meant that any adult convicted of people smuggling would spend a mandatory sentence in custody.

Adults by assumption

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) had used a highly inaccurate wrist x-ray technique to claim that the 14 and 16 year old were both 18 at the time. The AFP failed to undertake any investigations as to the age of the boys, apart from the x-rays.

Because of this technique, the boys were both charged as adults, and Peter O’Brien had to go to Indonesia himself to gather evidence of the children’s actual age.

The team went to the small village of Bau Bau to determine their age and obtain proof of age.

A key element to obtaining these details were sketched on the bottom of a trunk. The father of one of the boys carved the name and date of birth of his children on the underside of a trunk after their birth

Children thrown in with the worst of the worst

“Children detained with ‘the worst of the worst’” was the headline of the Sydney Morning Herald article.

“Indonesian children caught on people smugglers’ boats are spending up to 735 days in prison in Australia as police try to determine their age, a Senate committee has heard,” the article read.

“This is despite an agreement with the Indonesian government that children should not face Australia’s harsh mandatory sentencing laws for people smuggling and should be immediately returned home.”

In addition to Pak and Atok, Peter O’Brien has represented 13 other Indonesian children in similar circumstances. In each case, Peter was able to prove that the children were not adults.

Each of them has been in detention for more than 12 months, alongside rapists, murderers and paedophiles.

A long road to justice, and the nitty gritty legal stuff

The claim for false imprisonment was filed in 2012. Essentially, the argument from our firm was that the arrest of Pak and Atok was wrongful, so it followed that their detention by police prior to being refused bail was also wrongful.

The alleged crime of aggravated people smuggling is a Commonwealth offence (under the Migration Act 1958 s233C), hence the Commonwealth Crimes Act 1914 governs the criminal procedure surrounding that offence.

The rules of arrest are set out in Section 3W of the Crimes Act 1914. These rules state that arrest may only be carried out if a summons would not be adequate to ensure the appearance of the person before a court.

Pak and Atok were already lawfully detained in immigration detention. So, there was no risk of them not appearing before a court. A summons obviously would have been adequate; therefore, arresting the boys was wrongful.

Unlawful arrest equals unlawful criminal detention, and unlawful criminal detention is usually sufficient to make out a claim of false imprisonment.

The argument from the Commonwealth was that because the boys were already detained in immigration detention, they weren’t deprived of their liberty any more than they would have been in detention.

This interpretation of the Migration Act essentially claimed that children in detention, if charged with a crime, could be held anywhere that pleased the government.

O’Brien Solicitors answer to this objection relied on a previously unrecognised legal concept: residual liberty. Residual liberty states that even though a person may be otherwise lawfully detained, they still enjoy those civil liberties that are not taken away. One’s liberty does not wholly disappear when a person is first detained.

In Justice Hamill’s words, the concept of residual liberty is the “rejection of the alternative view, arising from a simple age, that liberty is all or nothing”. New, harsher forms of detention cannot be imposed simply because an individual is already detained: detention within detention must always be justified.

Delivering justice

On February 3, 2016 Justice Hamill handed down a verdict in favour of Pak and Atok on the basis of false imprisonment.

Peter O’Brien, alongside barristers Peter Strickland SC and Adrian Canceri, were overwhelmed with joy.

On 20 November 2016, Peter went to Indonesia to deliver the money which was promptly used to facilitate a renewable income for the village.

“They used the money to buy fishing boats for their village,” Mr O’Brien said.

“And the boats enabled them all to earn a living and the whole village turned out to thank him for “saving their future.”

*Names changed as the boys were minors at the time.

Sarah is a civil solicitor who primarily practices in defamation, intentional torts against police, privacy and harassment.

- Sarah Gorehttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/sarahg/

- Sarah Gorehttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/sarahg/

- Sarah Gorehttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/sarahg/

- Sarah Gorehttps://obriensolicitors.com.au/author/sarahg/