Australia’s Constitution as it stands protects only a limited number of rights. Most of them have been read as ‘implied rights’ by the High Court. Australians can find their human rights that are protected in the Constitution, in common law, anti-discrimination laws and other State and Federal legislation.

Australia’s Constitution as it stands protects only a limited number of rights. Most of them have been read as ‘implied rights’ by the High Court. Australians can find their human rights that are protected in the Constitution, in common law, anti-discrimination laws and other State and Federal legislation.

Our human rights are also protected through mechanisms such as an independent judiciary, a democratically elected government, a free media, a strong civil society and bodies such as the Australian Human Rights Commission who monitor these bodies.

There is a strong push for a succinct and clear legislative charter of human rights – is this a good idea?

“Human rights recognise the inherent value of each person, regardless of background, where we live, what we look like, what we think or what we believe.” – Australian Human Rights Commission.

HUMAN RIGHTS RECORD

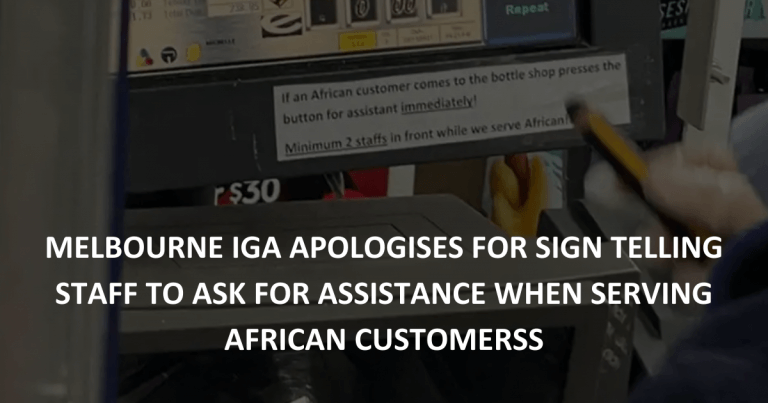

Despite current legislation and mechanisms, Australia’s human rights record is not strong. From poor health outcomes of Indigenous Australians to Indigenous deaths in custody, mandatory and indefinite detention of asylum seekers and the conditions for homeless people, Australia is far behind the times.

Australia is a party to the United Nations and often signs treaties that are passed through the body. However, treaties only become law once the country ‘ratifies’ it – this means they pass a law in parliament to make it a law in Australia. Australia has done so for a few treaties in the past, however, these laws create a patchwork. What’s missing is a clear and unifying codification of human rights.

Recently, the Government has come under fire for threats to press freedoms. Raids on the ABC and on News Corp journalist Anika Smethurst raise concerns for Australia’s secrecy functions. Taking this one step further, the Government has charged a lawyer, Bernard Collaery, after he gave legal advice to Witness K – a former ASIS officer turned whistle-blower. Not only is the fact that Mr Collaery has been charged a concern for human rights watchers, but the trial will be held in secret. Mr Collaery’s lawyer protested the decision stating that “open justice is an essential part of our legal system, the rights of defendants and our democracy.”

Since 2001, Australian Governments of both parties have granted unprecedented powers to security and intelligence organisations. According to President of the Australian Human Rights Commission Gillian Triggs, some examples of legislative overreach include:

- The Data Retention Act

- Foreign Fighters Act

- Espionage and Foreign Interference Act

- De-encryption provisions

- Laws expanding detention for questioning

- Secrecy laws applicable to offshore detention and security operations

RIGHTS-CENTRIC APPROACH

A clear piece of legislation stating all the rights afforded to Australians would create a more rights-centric approach, with more people understanding the rights they hold. This, in turn, would place more pressure on Governments and Authorities to uphold these rights.

A Charter of Rights could act as a symbol. For those currently struggling with the protection of their rights, the Charter could empower their ability to raise issues without the necessity of intricate legal work not often available to those parties.

The UK Human Rights Act provides a good framework. The Act gives courts clear guidance when rejecting laws passed in the name of national security that breach these rights.

STATUTORY PROS AND CONS

Understandably there are concerns to a charter of rights flagged by the obvious failings of the Bill of Rights in the USA. The bill holds out of date social constructs as inherent rights that can not easily be changed. However, a statutory Charter of Rights can be altered by Parliament – hopefully avoiding these types of issues. This has a trade-off, meaning of course that the Parliament could change these rights at any point.

Any statutory charter of rights can be exploited – just like any constitutional charter of rights can be exploited too. A statutory charter gives Courts a greater power to hold the Government to standard – however it is not immune from dictatorship.

Should Courts be given more power? While Courts can be viewed as rational objective bodies, the truth can be more complex. Judges are also unelected and instead selected by a panel – this can raise eyebrows as to whether they should be making such important decisions on matters of social justice or public interest.

However, as Gillian Triggs sums up:

“It would be a misunderstanding of the role of a rights charter to think only of judicial power. The real significance of a charter lies in the benchmarks it creates to influence the decisions of public officials and the standards demanded by the community. A charter is a check on government power that is vital to contemporary democracy.”